Blog

What’s on our minds

We share what we learn and what we’re doing so that others can learn from us and we can learn from others. Comments welcome!

Moving from “Someone should do something” to “I can do something”

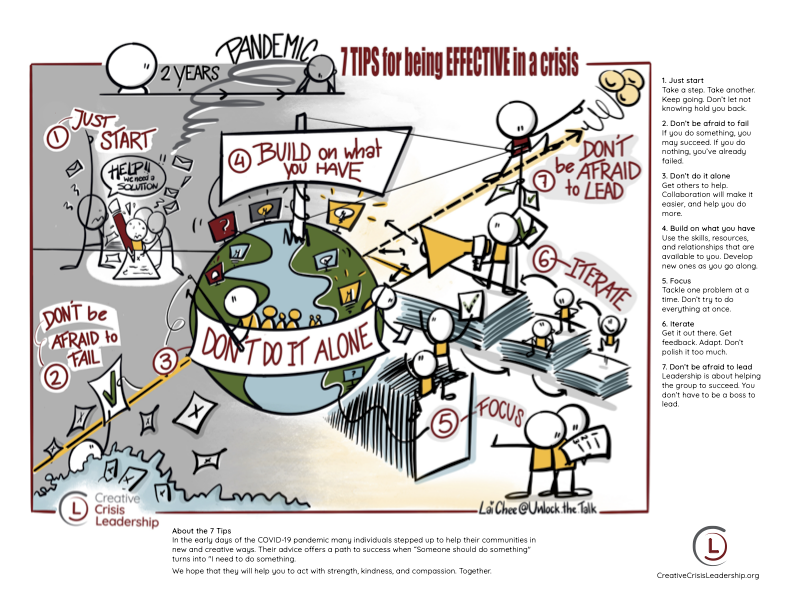

In tribute to my family in Minneapolis, we are sharing our “7 Tips for Being Effective in a Crisis.” These insights come from our study of individuals who stepped up during the COVID-19 pandemic to help their communities.

We hope they inspire others to help their neighbors with grace, caring, and dignity — turning “someone should do something” into compassionate action.

May we all embrace “Minnesota nice.”

— Susanne

Help wanted: Be part of the Wildfire Fun Team!

We are looking for a volunteer or two to help us run the Wildfire Board Game at some upcoming events:

- March 7: Steelhead Festival (Lake Sonoma Recreation Area)

- April 26: Sonoma County Wildfire & Earthquake Expo (Santa Rosa)

- May 2: Solano County Preparedness Fair (Location TBD — last time we attended it was at Lake Solano County Park)

We’ll make sure it’s a smooth (and free!) experience: We provide full training on the game, and can reimburse travel mileage, plus lodging and meals if the event is more than 50 miles from home.

If you are interested, or know someone who is, please get in touch. Anyone with a background in wildfire preparedness would be a natural. Having a Spanish speaker on the team would be a huge win for reaching the whole community.

Have fun while helping communities to become more wildfire resilient!

Curiosity #12: A Burning Need — Why the Forest is Pro-Fire

![]()

While humans view wildfire as a purely destructive force to be stopped at all costs, many of our forest neighbors can’t live without it. For “pyrophilic” species, a total ban on fire isn’t a safety measure — it’s an extinction event.

To understand the forest’s needs, let’s hear what its inhabitants might have to say about a total ban on wildfire.

THE DAILY DUFF — The stuff you need to read

SACRAMENTO — In a resin-scented showdown yesterday, the forest took to the streets to protest the proposed “No More Wildfire” bill. Thousands of species gathered for a Pro-Fire rally at the Capitol, arguing that for them, fire isn’t a disaster — it’s a life-giving necessity.

The air buzzed with insects and rustled with needles as pyrophiles (fire-lovers) from every corner of the state demanded their right to burn. The protest centered on a single, vital truth: Many species are fire-dependent. Without the heat of a blaze, they cannot survive.

A Demand for Reproductive Rights

The morning’s energy peaked when a tall, slender Lodgepole pine, who requested anonymity for fear of pruning, spoke out with visible passion. “Fire is life,” the pine hissed through its needles. “I, and my fellow pyrophiles, need heat to reproduce. We demand the right to burn!”

The crowd erupted into a rhythmic clashing of branches as the Society of Serotinous Plants stepped forward to explain the biological stakes. A spokeslimb noted that for members like the Lodgepole, seeds are held “hostage” in resin-sealed cones. Without the intense heat of a wildfire to melt that wax, the seeds remain trapped indefinitely. Only fire, they argued, triggers the “seed rain” necessary to colonize the fresh, nutrient-rich ash left in a fire’s wake.

The Sexy Side of Smoke

Nearby, a group of beetles held up a sign, “SMOKE and ASH are SEXY.” Firechaser beetles mate exclusively in smoke and lay eggs in scorched wood. Their spokesbug explained that their infrared sensors allow them to detect a fire as far as 30 miles away.

Overhead, a wing of woodpeckers trailed banners saying, “BURNS are AFFORDABLE HOUSING.” Black-backed woodpeckers use the scorched snags to build nests free from the tree’s sticky, defensive sap.

A Call for Balance

The crowd fell silent as Dr. Venerable Oak took the podium. In a voice like shifting tectonic plates, he explained that fire is the forest’s cleaning and catering service. “Fire takes out the garbage,” he boomed. “It clears the dead wood that chokes our soil. Through mineralization, fire converts waste into vitamins, including potassium, calcium, and magnesium. It releases nitrogen and carbon back into the earth so all our fire-following siblings can carpet the ground in green once more.”

He concluded with an appeal for inclusiveness and unity, “We are in the forest together. To survive, we must respect and care for each other. There must be balanced fire and forest management, a total ban will be the death of us all.”

Despite a group of counter-protesters wearing “Smokey Bear” hats and waving fire extinguishers, the Pro-Fire rally remained peaceful. As the sun set, the message was clear: Fire is a destructive force, but for the forest, it is also a force of life. To ban it entirely is to ban the future of the ecosystem.

What can you do?

BEFORE the fire: Support expert-controlled burns and healthy fire ecology to manage fire risk and encourage biodiversity.

DURING the fire: Stay safe.

AFTER the fire: Celebrate regrowth, plant native species, and watch nature’s magic. Avoid crushing delicate new life with renegade trails through burned areas.

RIGHT NOW: Make a donation to help Creative Crisis Leadership turn complex science into simple, life-saving knowledge!

Sources

- The Ecological Benefits of Fire | National Geographic

- How Does Wildfire Affect Soil and Vegetation? | Western Fire Chiefs Association

- Science: Wildfire Impacts | California Department of Fish and Wildfire

- Wildfire Benefits Many Bird Species | Audubon

- Fire Effects Information System | USDA Forest Service

Stay Safe and Be Curious this Holiday Season!

Curiosity #11: Wildfire and the Secret Life of Steel and Stone

Have you ever looked at a massive concrete bridge and thought, “That’s basically rock, it’s invincible”?

Concrete is generally a firesafe material:

“Concrete and concrete products are fire resistant. Concrete does not burn and it does not emit any toxic fumes when affected by fire. Concrete is inert and in the majority of applications, can be described as virtually fireproof.”

— Wildfires and What They Mean for You | How Concrete Can Help | Intelligent Concrete

But, while it doesn’t burn, concrete is not impervious to fire. [Concrete … impervious … get it? 😛] When concrete is exposed to high temperatures, it doesn’t just heat up, it begins to change at the molecular level.

The intense heat of a wildfire can turn a solid structure into a safety hazard.

Let’s look at the Secret Life of Steel and Stone.

Sweating Concrete

Concrete isn’t as solid as you think. It’s actually a composite of cement, aggregates (sand and gravel), and water. When it’s first made, a chemical reaction called hydration locks the water into the structure to give it strength.

Fire essentially “dehydrates” the stone. At a molecular level, the heat reverses the process that made the concrete strong in the first place: At 300°F, the internal water “sweats” out, micro-cracks form, and the concrete begins to weaken. At 800°F, the cement paste — the glue holding the rocks together — begins to break down. At 1,000°F+, the structural integrity is effectively gone.

(Pro tip: The oven in your kitchen tops out at 550°F. Wood bursts into flames at 570°F. A wildfire may roar at 2,000°F, it’s really really hot!)

Under Pressure

Because concrete is porous (or should we say, “pervious”? 😉), the water trapped inside turns to steam. If the fire is hot enough, that steam can’t escape fast enough. Pressure builds until chunks of concrete literally explode off the surface. This is called spalling.

(Pro tip: Don’t stand next to concrete if it’s really really hot!)

A Heart of Steel

But what about the rebar inside that cement? The heart of steel that carries all the weight?

Well, that steel is heating up, too. At 700°F, it begins to lose its temper. By 1,000°F, it can carry less than 60% of its designed weight.

(Pro tip: Don’t stand on that bridge if it’s really really hot!)

The Invisible Sag

As the steel heats up, it softens, and starts to stretch and sag. Once steel sags and then cools down, it stays in that new, weakened shape. After a fire, that bridge might look perfectly fine, but structurally be bent out of shape and about as reliable as a wet noodle.

(Pro tip: If the engineers say it isn’t safe, really really believe them.)

What can you do?

BEFORE the fire: Use fire-rated materials for hardscaping and home construction, particularly for roofs and areas within 5 feet of your home.

DURING the fire: Follow official evacuation routes strictly, they may be directing you around unsafe overpasses, compromised bridges, and other hazards.

AFTER the fire: Stay away from scorched concrete walls or chimneys, they may be unstable. If a structure has been exposed to high heat, assume it is unsafe until a professional inspection clears it.

RIGHT NOW: Make a donation to help Creative Crisis Leadership turn complex science into simple, life-saving knowledge!

Sources

- Wildfires and What They Mean for You | How Concrete Can Help | Intelligent Concrete

- Alhamad, Amjad, Sherif Yehia, Éva Lublóy, and Mohamed Elchalakani. “Performance of different concrete types exposed to elevated temperatures: a review.” Materials 15, no. 14 (2022): 5032.

- FiRE!!! and concrete | Tyler Ley

- Spalling of Concrete in a Fire | Tyler Ley

Stay Safe and Be Curious this Holiday Season!

Curiosity #10: Caging the Wildfire Dragon

There is a wildfire dragon rampaging through the forest. Dragon Slayers are fighting hard to stop it. But dragons are hard to kill. Battling them can go through many stages.

In the world of wildfires, firefighters have very specific words for the different stages of battling the Dragon. Understanding these terms—Contained, Controlled, and Out—is crucial for managing your expectations and knowing what is safe to do when smoke is in the air.

Stage 1: Contained

The dragon is ferocious. The fearless and valiant dragon slayers are fighting hard, but they just cannot put the powerful beast down. Undeterred, they prudently back off and try to contain the fearsome creature by building a “cage” around it.

A fire is Contained when it is encircled by a fuel break — a strip of land that has been cleared of vegetation and other flammables to slow the fire spread. This break may comprise roads, rivers, or swathes of bare dirt scraped clean by bulldozers.

But a fire may only be partially contained: When you hear a fire is “65% contained,” it doesn’t mean 65% of the fire is out. It means firefighters have created containment lines — fuel-free boundaries — along 65% of the wildfire’s perimeter.

When a wildfire is fully contained, there is a completely closed perimeter of fuel breaks surrounding it. At this stage, there is a “reasonable expectation” that the dragon won’t break out of the cage. But inside that ring? The wildfire is still actively burning. The angry dragon is still raging and could escape.

Stage 2: Controlled

Now that the fearsome beast is fully contained in a cage, the battle-hardened dragon slayers work to beat it back until they can kill it outright, or it starves to death

A fire is Controlled when the containment lines are holding strong, and crews have extinguished every flame, ember, and smoking twig within 300 feet inside the perimeter. The weary dragon is exhausted and is unlikely to escape. The fatiguing dragon slayers heave a sigh of relief, but the dragon is not out yet.

Stage 3: Out

Finally, the starving dragon is weak enough for the dragon slayers to take it on directly. With a final mighty thrust of their lances, they kill it. The wildfire dragon is finally dead!

A fire is Out when there have not been any active flames or smoldering, smoking hotspots for at least 48 hours anywhere inside the perimeter. However, for many wildfires, fire fighters may monitor the burn area for a much longer period of time before they declare that the fire has been fully extinguished and poses no risk of reigniting. In massive wildland fires, crews might patrol the area for weeks until heavy rain or snow guarantees the job is done. Only when the exhausted dragon slayers feel it is safe to put away the lances and go home, do they declare the dragon dead.

Epilogue

But! You know how all horror films end! The dragon may still come back as a zombie fire and live to burn another day. Under certain conditions, heat can burrow deep into root systems or peat soil. There, underground, the wildfire dragon survives, insulated by the earth, smoldering quietly while snow falls above it, patiently awaiting its chance to return. Bwaa hah hah…

What can you do?

- BEFORE the fire: Sign up for local emergency alerts, and learn the terminology so that you understand updates and can make good decisions when the time comes.

- DURING the fire: Monitor and follow directions from official incident maps and sources of information.

- AFTER the fire: Beware of burned land even after the fire is “Out.” Root systems may still be weak or smoldering deep underground.

RIGHT NOW: Make a donation to help Creative Crisis Leadership turn complex science into simple, life-saving knowledge!

Sources

- NWCG Glossary of Wildland Fire, PMS 205 | National Wildfire Coordinating Group

- How Authorities Define Fire ‘Containment’ and ‘Control’ | TIME

- What Does Wildfire Containment Mean & How is it Measured? | WFCA

- Wildfire “Containment” Explained | RedZone

Stay Safe and Be Curious this Holiday Season!